Detailed Experiment Description for False Positives and False Negatives Analysis

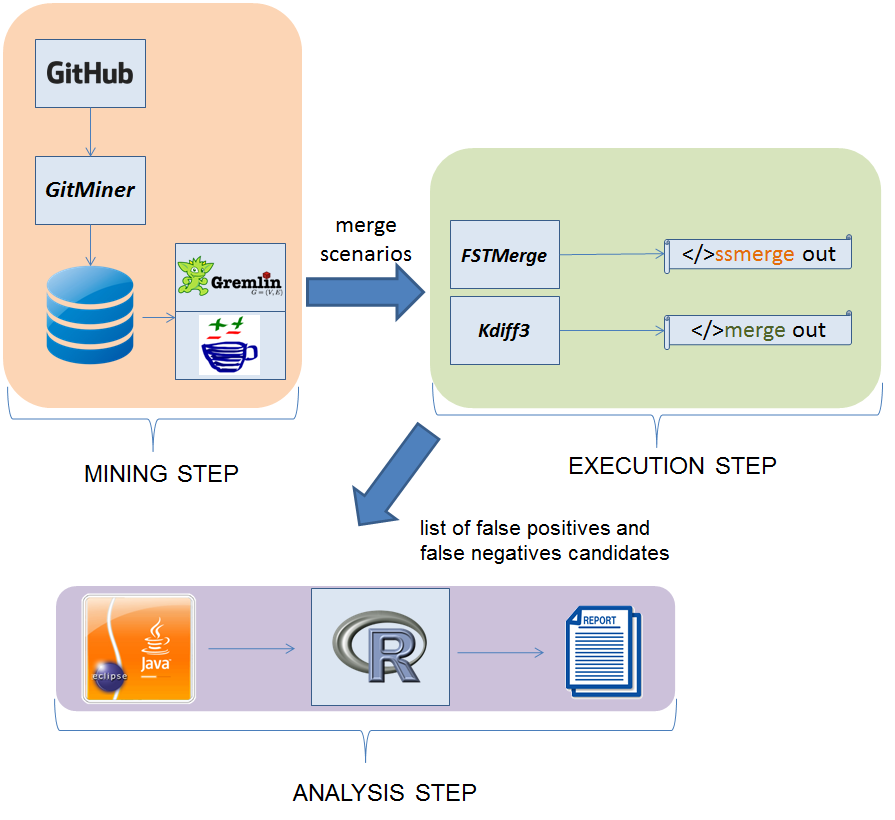

To answer our research questions and compute the related metrics, we design the experiment illustrated in the figure above. In the mining step, we use tools that mine Distributed VCS repositories to collect a number of merge scenarios. Subsequently, in the execution step, we use merge tools from both approaches in order to merge the selected merge scenarios and to find false positives and false negatives candidates. Afterwards, in the analysis step, we parse and compile the files to which the false positives and false negatives candidates belong to confirm their occurrence. Finally, we use R scripts to sum up the results. In this online appendix, we explain the details about the execution and analysis steps, details about the mining step is available in the paper.

Experiment Design

Execution and Analysis Steps

After collecting the sample projects and merge scenarios in the mining step, we use both unstructured and semistructured approaches to merge the selected scenarios and to find the false positives and false negatives described in the paper. In the following we explain how we collect each metric.

Overestimated Number of False Positives Added by Semistructured Merge — aFP(SS)

The semistructured merge added false positives are due to renamings. They happen, for instance, when one of the developers edits the body of an existing method from the base revision, and the other developer modifies its signature. In the following paragraphs we explain how we identify such false positives, and why this metric is an upper bound.

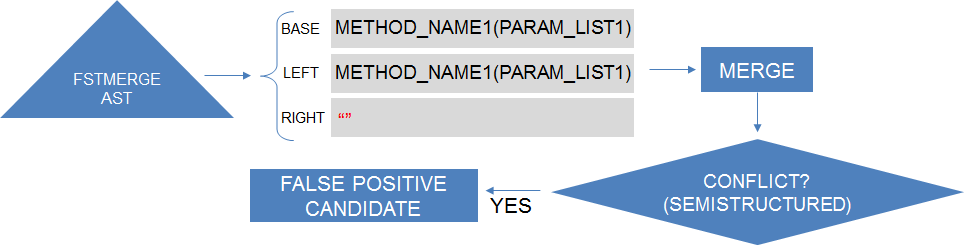

As programs elements are nodes in the generated AST of the FSTMerge tool, to identify these false positives, we first intercept conflicts detected by FSTMerge and check whether the involved triple of base, left and right elements contains a nonempty base, and an empty left or right element. Not having the left or right version, represented by the red empty string in the figure bellow, indicates that the semistructured merge algorithm could not map the element (method in this case) to its previous version, either because the element was renamed or deleted. Since we cannot precisely guarantee there was a deletion (the best option would be a similarity analysis on method bodies), we conservatively analyze all such cases.

Intercepting FSTMerge tool to find false positives (aFP(SS)) renaming/deletion conflict candidates.

To filter out obvious renaming true positives, we consider as added false positives only cases with no remaining references to the renamed or deleted element. For efficiency and simplicity, we conservatively check that by parsing the merged revision files and looking for nodes that refer to the original signature of the renamed or deleted element. More precise analyses with call graphs, and verifying that the existing references are not part of dead code, would still be incomplete and would compromise our sample size because of both performance overhead and the need for building projects. That is why we opt for computing the overestimated number of false positives added by semistructured merge.

Underestimated False Negatives Added by Unstructured Merge — aFN(UN)

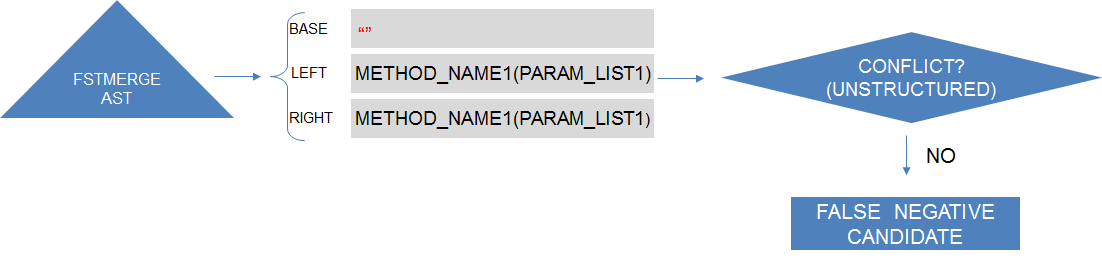

The main pattern of unstructured merge added false negative occurs when developers introduce duplicated declarations in different areas of the program text. To identify such situations, by intercepting FSTMerge's execution, we look for triple of matched elements in which the base version of the element is empty and the left and right are not (see the figure bellow). Such pattern indicates that there are two elements with the same name not present in the base revision of the code. Then, for each identified triple, we check if unstructured merge reports a conflict a containing the identifier of the possibly duplicated element (for example, a method signature). When we cannot find a conflict with such characteristic, unstructured merge was able to integrate the two versions of the element, or there might be a duplication. We check that by using Eclipse AST's compilation features to compile the file containing the observed duplication candidate merged by unstructured merge. Finally, we search for compilation problems corresponding to duplicated declaration error related to the observed candidate. In case of finding such compilation problem, we consider an occurrence of false negative.

Whereas we are able to precisely compute the number of duplicated declaration errors, it would be harder to precisely compute other kinds of false negatives--- such as true renaming conflicts--- missed by unstructured merge.

Intercepting FSTMerge tool to find false negatives (aFN(UN)) duplicated declaration error candidates.

Overestimated Number of False Negatives Added by Semistructured Merge — aFN(SS)

Semistructured merge reduces some of the false negatives of unstructured merge due to the detection of duplicated declarations, but it adds some too. In particular, the false negatives added by semistructured merge are related to three major causes: reordering import statements that involve types with the same identifier, not matching initialization blocks, and unstructured merge accidental conflict detection.

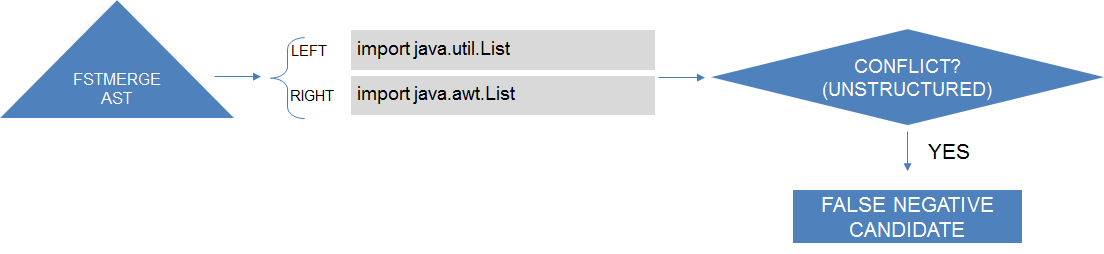

Beginning with the false negatives related to the import statements, they can occur in three situations, which we describe bellow, explaining together how we identify them. As illustrated in the figure bellow, by intercepting FSTMerge execution, we identify pairs of nodes representing import statements introduced by different developers in the files being merged by semistructured merge. Afterwards, we check if the identified pairs are (1) involving members with the same name, as in import java.util.List and import java.awt.List. We also look if the identified pairs are (2) pairs of import statements of entire packages as in import java.util.* and import java.awt.* (as long as the packages have a member in common). Finally, whereas these previous cases lead to build problems, (3) we compute a case that can lead to behavioral errors instead (which is even worse). Such cases happen when one of the developers imports all members from a package, and the other developer imports a member with the same name of an existing member in the package imported by the first developer. For instance, one writes import java.awt.* and the other writes import java.util.List, where the package java.awt.* also has a member named List. These pairs of import statements can only be a false negative added by semistructured merge if they are added in the same area of the text, otherwise it would be a false negative of the two approaches. This way, we check in the corresponding file merged by unstructured merge if there is a conflict involving the pair of imports statements.

Intercepting FSTMerge tool to find false negatives (aFN(SS)) type ambiguity error candidates.

The first and second cases described in the previous paragraph only lead to type ambiguity errors when, in the presence of those pairs, the rest of the code refers to the imported elements using its abbreviated name as in List list = new List(). We check that by using Eclipse AST's compilation features. We compile the files merged by semistructured merge and that have the a pair of import statements as just described, and we search and account the compilation problems corresponding to type ambiguity error. Regarding the third case, we approximate the verification by checking if the changes introduced by the developer who imported all members from the package contain the name of the member imported by the second developer.

To identify the second kind of false negative, we select all nodes representing initialization blocks in the three versions of the trees representing the files being merged. Using textual similarity, based on the Levenshtein distance algorithm with 80% of degree of similarity, we group triples of similar initialization nodes in the different tree versions. Lastly, we merge these triples with unstructured merge. If they conflict with unstructured merge, we conservatively classify the conflict as a semistructured merge added false negative.

All other cases of conflicts detected by unstructured merge but not by semistructured merge are conservatively classified as added false negatives except in the following two cases when the unstructured merge conflict can be parsed. First, when the conflict contains only field declarations that do not reference each other. Second, when the conflict resolution keeps all changes from both left and right revisions, and adds no new code; we check that by parsing and inspecting the original merge commit in the project repository. We assume that the developer correctly analyzed the conflict and decided there was no interference; so that would be a unstructured false positive, not a semistructured false negative.

Underestimated Number of False Positives Added by Unstructured Merge — aFP(UN)

The false positives added by unstructured merge in comparison to semistructured merge are due to changes in the order of commutative and associative declarations --- the ordering conflicts. We explain bellow how we compute such false positives, and why this metric is a lower bound. In particular, there are no specific patterns of ordering conflicts that would allow us to identify them systematically. Thus, we compute this metric in function of the other ones.

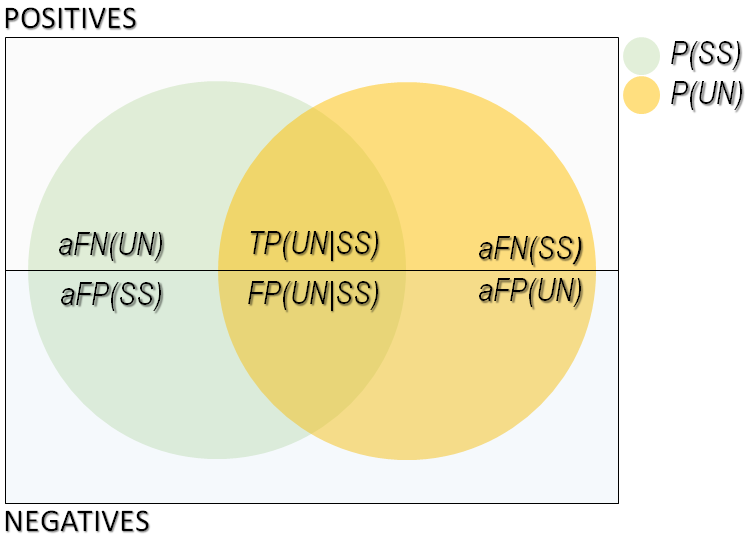

In the diagram of the figure bellow, we illustrate the set of conflicts emerging from development tasks reported by unstructured and semistructured merge. Observe that each merge approach has its own set of reported conflicts. For instance, unstructured merge's set includes its own false positives (aFP(UN)), and false negatives added by the semistructured approach that unstructured merge is able to detect (aFN(SS)). The sets also includes true positives and false positives common to both approaches (TP(UN|SS) and FP(UN|SS)). Looking at these sets, we can infer how to calculate the false positives added by unstructured merge. In particular, from the diagram, note that:

Set of conflicts reported by unstructured and semistructured merge

- P(UN) = FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS) + aFP(UN) + aFN(SS)

From which follows that,

- aFP(UN) = P(UN) - (FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS)) - aFN(SS)

In order to aFP(UN) be a lower bound, we need an upper bound of (FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS)) because it is a subtractive factor. If we look at how P(SS)} is composed, we see that:

- P(SS) = FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS) + aFP(SS) + aFN(UN)

Therefore,

- FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS) = P(SS) - aFP(SS) - aFN(UN)

Note that,

- FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS) + aFP(SS) = P(SS) - aFN(UN)

Thus, an upper bound of (FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS)) happens if aFP(SS) is at its minimum possible value (zero). Therefore, the upper bound of (FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS)))) is given by:

- FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS) ≤ P(SS) - aFN(UN)

Finally, replacing (FP(UN|SS) + TP(UN|SS)) in the formula of aFP(UN) given above, the minimum number of false positives added by unstructured merge becomes:

- aFP(UN) ≥ P(UN) - P(SS) + aFN(UN) - aFN(SS)